A trade deficit occurs when a country buys more from the rest of the world than it sells. In simpler terms, the value of its imports is greater than the value of its exports. It’s a lot like a household spending more money than it earns in a given month—on a national scale, this imbalance is known as a trade deficit.

However, a deficit is merely a single aspect of a broader issue.

Decoding the Balance of Trade

Understanding the balance of trade is crucial for comprehending a trade deficit. Think of it as an economic scorecard that tracks the total value of a nation’s exports against its imports over a certain period. It’s one of the most fundamental metrics for gauging how a country interacts economically with its global partners.

A country’s trade balance can land in one of three states, and each one tells a very different story about its economic position on the world stage.

The Three States of Trade Balance

While the trade deficit often grabs the headlines, it’s not the only outcome. A nation’s trade can also result in a surplus or, theoretically, be perfectly balanced.

Let’s break them down:

- Trade Deficit (Negative Balance): This occurs when a country’s imports exceed its exports. A country is essentially purchasing more goods and services from other nations than it’s selling to them. For example, if the U.S. imports $350 billion in goods but only exports $280 billion, it has a $70 billion trade deficit.

- Trade Surplus (Positive Balance): Here, the opposite is true: Exports > Imports. The country is selling more to the world than it’s buying. Nations like Germany and China have historically run significant trade surpluses, exporting high volumes of manufactured goods.

- Balanced Trade: A surplus is the ideal state where exports equal imports. The value of goods and services leaving the country perfectly matches the value of those coming in. In reality, given the constant flux of the global economy, achieving a perfectly balanced trade is exceptionally rare.

To make the situation even clearer, the following table summarizes the key distinctions.

Trade Balance at a Glance

| Trade Status | Condition | Economic Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Trade Deficit | Imports > Exports | The country consumes more than it produces for the world. |

| Trade Surplus | Exports > Imports | The country produces more for the world than it consumes. |

| Balanced Trade | Exports = Imports | Production for the world market equals domestic consumption of foreign goods. |

This table provides a quick reference, but remember that these numbers aren’t just abstract figures; they reflect tangible economic realities.

Macroeconomic fundamentals ultimately determine a country’s external balance. Both trade surpluses and deficits are often homegrown, reflecting domestic savings, investment, and consumer demand rather than just trade policies alone.

It’s also worth noting that the picture can be more nuanced. For instance, the United States has consistently run a large deficit in physical goods (like electronics and automobiles) while simultaneously maintaining a healthy surplus in services (like software development, financial services, and tourism). Grasping this distinction is key to a truly comprehensive understanding.

The Real Reasons Behind a Trade Deficit

Trade deficits are not the result of random events. They’re the outcome of powerful economic forces at work, both within a country’s borders and across the globe. Despite the temptation to blame trade policies, the true cause often lies in a nation’s domestic economic health and the international money flow.

One of the primary drivers is actually a strong domestic economy. When people feel positive about their finances and businesses are expanding, they spend more. This surge in demand isn’t just for locally made products; it also creates a healthy appetite for imported goods, from European cars to the newest smartphones from Asia.

This scenario leads to what feels like a paradox. A thriving economy—something everyone wants—can directly cause the trade deficit to grow because imports start to outpace exports. It’s a sign that a nation has the wealth and confidence to consume more than it produces, often bankrolled by optimistic foreign investors.

The Influence of Currency and Costs

The value of a country’s currency in the global arena also plays a significant role. A strong U.S. dollar, for instance, makes foreign goods cheaper for Americans. The result is a simple but powerful incentive that boosts imports. Conversely, a strong U.S. dollar increases the cost of American-made products for everyone else, potentially hindering export sales.

A country’s external surpluses and deficits are mostly homegrown. They are ultimately determined by macroeconomic fundamentals like domestic savings and investment, not just trade policy.

Both sides exert pressure on the trade balance, thereby widening the gap. Currency strength is tied to all sorts of factors, like interest rates and investor sentiment, which means the trade balance is deeply connected to a nation’s overall financial stability.

National Savings and Investment Habits

Ultimately, a country’s collective financial habits are a major factor. The link between how much a nation saves versus how much it invests is fundamental to understanding what a trade deficit is from a big-picture perspective.

Think about it in these two ways:

- Low National Savings: When a country’s citizens, companies, and government collectively spend more than they save, they often need to borrow from other countries to pay for investments (like new factories or infrastructure). This influx of foreign money is the financial counterpart to a trade deficit.

- High Investment Demand: A nation bursting with profitable investment opportunities might attract more foreign capital than its own people can supply through savings. This demand for investment funds finances the very imports needed to fuel that growth.

At its core, a trade deficit is an accounting identity that shows a nation is investing more than it’s saving. The United States, for example, has long had relatively low household savings rates and significant government budget deficits, which are key reasons for its persistent trade deficit. In contrast, countries with very high savings rates, such as China, often run the opposite: a trade surplus. These are the powerful, deep-seated forces driving the trade numbers you read about in the news.

A Historical Look at Trade Imbalances

Trade imbalances are nothing new. In fact, they’ve been a constant feature of the global economy for centuries, shifting with major world events, policy changes, and the very structure of how countries do business with one another. Looking at the history of the United States provides a fantastic case study of how these deficits and surpluses ebb and flow over time.

For a long time after World War II, the U.S. consistently ran trade surpluses. This made perfect sense—its manufacturing power was unmatched, and it played a huge role in rebuilding a war-torn world. But that picture started to change dramatically in the second half of the 20th century. The 1970s, with its oil price shocks and the rise of powerful new competitors in Europe and Japan, marked a major turning point.

The Rise of Persistent Deficits

By the 1980s and 1990s, the trend toward running a trade deficit was no longer a blip; it was becoming the new normal. Globalization was in full swing, creating the complex international supply chains we know today. American companies, looking to cut costs, started moving manufacturing to countries with cheaper labor, which naturally led to a surge in imported goods. At the same time, a strong U.S. economy and easy access to credit meant American consumers were buying more than ever, widening that trade gap even further.

A country’s external balance is a mirror of its internal economic conditions. The long-term shift toward a trade deficit in the U.S. reflects deeper changes in national savings, investment patterns, and its evolving role in the global economy.

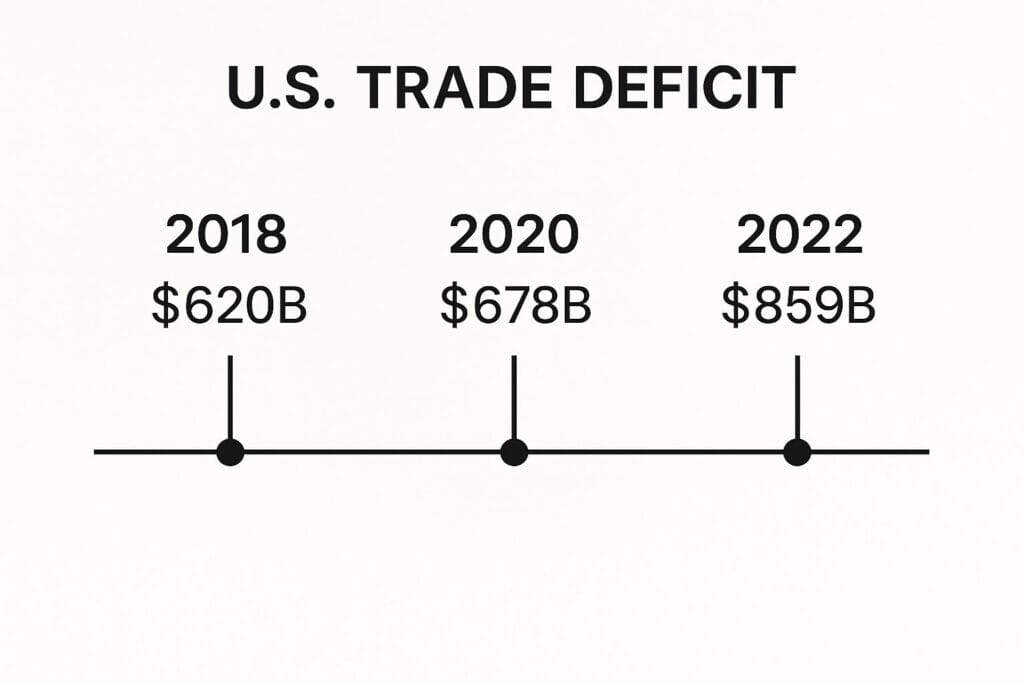

These historical currents laid the groundwork for the large, persistent deficits that characterize the modern era. As you can see in the timeline below, the U.S. trade deficit hasn’t just grown—it has exploded in recent years.

This chart drives the point home: the U.S. trade deficit ballooned by nearly 40% in just four years, a staggering acceleration.

Understanding the Modern Context

U.S. trade deficits have always swung back and forth, pushed and pulled by the strength of the domestic economy and specific government policies. If you look at the long-term data, the average monthly trade balance from 1950 to 2025 sits at around -$18.95 billion, showing a clear historical lean towards deficits.

Of course, there have been extremes. The U.S. posted its largest-ever surplus of $1.95 billion way back in June 1975. On the other end of the spectrum, it hit a record-breaking deficit of -$138.32 billion in March 2025, a result of tangled supply chains and chaotic global demand. You can dive deeper into these historical figures and see future projections over at Trading Economics.

But this history isn’t just a story told in numbers; it’s about the intricate dance between national economies. The trade relationship between the U.S. and China, for instance, has become one of the most defining—and contentious—features of the global economy. To get a better handle on this critical dynamic, it’s worth exploring the ongoing tariff negotiations and their global impact. Without understanding this historical context, today’s headlines about trade simply don’t make much sense.

Seeing Global Trade Imbalances in Action

Trade deficits and surpluses aren’t just dry theories you’d find in an economics textbook. They are dynamic forces shaping our world every single day. Think of it as a global seesaw: for every country with a large trade deficit, there’s another with a surplus. It’s a fundamental reality of international accounting.

The United States is a perfect real-world example. For decades, it has run one of the largest trade deficits on the planet, meaning American consumers and businesses consistently buy more from other countries than they sell to them. On the flip side, you have nations like China and Germany, who typically run massive surpluses by acting as the world’s leading exporters.

The Major Players and Their Roles

To really grasp what a trade deficit is in a practical sense, you have to look at these relationships. A few economic giants dominate global trade, and their policies and consumer habits send ripples across the entire system.

- The United States (The Major Deficit Nation): Driven by robust consumer spending and an appetite for imported goods, the U.S. has become the world’s primary consumer. Its deficit is a direct reflection of an economy where spending and investment consistently outstrip savings.

- China (The Major Surplus Nation): Often called “the world’s factory,” China maintains a colossal trade surplus by exporting an incredible volume of manufactured goods. High national savings rates, lower production costs, and export-focused policies all fuel this surplus.

- Germany (A European Surplus Power): Germany is another export titan, renowned for its high-end industrial machinery and automobiles. Its persistent surplus, both within the European Union and globally, stands in stark contrast to the consumption-heavy model of the U.S.

While these roles can shift, they define the core dynamics of global trade today. The U.S. deficit creates a vast market for China’s surplus, forging a symbiotic relationship that is often fraught with tension.

A country’s external trade balance is a mirror image of another’s. Global trade is a closed system, meaning the sum of all deficits must equal the sum of all surpluses. One cannot exist without the other.

Geopolitics and Trade Numbers

Trade relationships are rarely straightforward; they’re constantly influenced by political friction and strategic maneuvering. These imbalances often find themselves at the center of critical international debates.

For example, global trade expanded by $300 billion in the first half of 2025, but that growth wasn’t shared equally. Developed economies actually saw their deficits grow, while countries like China and the EU expanded their surpluses. The U.S. trade deficit with China hit $360 billion annually, alongside a $276 billion deficit with the European Union and $116 billion with Vietnam. These figures spotlight just how significant some of these bilateral imbalances have become.

These widening gaps are occurring even as new tariffs and geopolitical tensions threaten to disrupt deeply interconnected global supply chains. You can dig into the numbers and policy risks yourself by exploring the latest global trade updates from UNCTAD.

Policies like protective tariffs on steel or the formation of regional trade pacts directly sway these numbers, turning economic data into front-page news. This complex interplay proves that a trade deficit is never just about the math—it’s about international relations, too.

How to Read a Trade Deficit Report

At first glance, a trade deficit report can look like an intimidating wall of numbers. It’s one thing to understand the concept in theory, but it’s another to stare at a government release and figure out what it all means.

But here’s the secret: these reports tell a story. They follow a simple logic, and once you know the plot, you can easily follow along.

At its heart, the math is straightforward: Total Imports – Total Exports = Trade Balance. If the number is negative, you have a deficit. If it’s positive, you have a surplus. The real skill is looking past that single number and digging into the two key components that create it: goods and services.

A country’s trade balance is rarely a monolith. It’s quite common for a nation to have a huge deficit in physical goods while, at the same time, running a healthy surplus in services. This contrast reveals a lot about the true strengths and weaknesses of an economy.

Dissecting the Numbers

Let’s walk through a real-world example to see how this works in practice. Official reports, like those from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, give you a detailed breakdown that paints a much clearer picture of what a trade deficit is.

Take the U.S. trade data from May 2025 as a perfect case study. In that month, the country posted an overall trade deficit of $71.5 billion.

How did we get there? Imports clocked in at $350.5 billion, while exports lagged behind at $279.0 billion. That big headline number tells us there’s an imbalance, but the truly interesting part comes when we split it between goods and services.

What the data actually reveals are two completely different economic narratives playing out simultaneously:

- Goods Deficit: Here, the deficit was a massive $97.5 billion. This tells us the U.S. bought far more physical products—cars, electronics, clothes—from the world than it sold.

- Services Surplus: On the flip side, the country ran a $26.0 billion surplus in services. This highlights a powerful competitive edge in areas like finance, intellectual property, and technology consulting.

This two-part view is absolutely essential for a proper understanding. It shows that while the U.S. is a huge net importer of physical things, its service sector is a global export powerhouse. Reading a report this way helps you see the nuances and understand how factors like international trade barriers might squeeze one part of the economy while leaving another untouched.

Are Trade Deficits Good or Bad for an Economy?

Ask a room full of economists whether a trade deficit is good or bad, and you’ll likely spark a heated debate. There’s no easy answer here. A deficit’s impact hinges entirely on the economic context driving it—it could be a red flag signaling structural problems or a sign of a strong, thriving economy.

To really get to the heart of this, it helps to look at a trade deficit from two completely different angles. On one hand, it can be a symptom of trouble ahead. On the other, it can reflect economic muscle and happy consumers.

The Case Against Trade Deficits

Critics often sound the alarm about long-term trade deficits, pointing to the real-world consequences for domestic industries and national finances. When a country consistently buys more than it sells, its own producers can get squeezed out.

The main concerns usually boil down to a couple of key issues:

- Pressure on Domestic Industries: If imported goods are cheaper, they can easily undercut local businesses. This can lead to factory closures and job losses, especially in manufacturing, slowly eroding a nation’s industrial strength.

- Increased National Debt: A trade deficit has to be paid for somehow. This is done through a “capital account surplus,” which is just a technical way of saying the country is borrowing from abroad or selling off its assets to foreign investors. Over time, this piles on debt to the rest of the world.

A trade deficit is the mirror image of a capital surplus. A country that consumes more than it produces must finance that gap by borrowing from abroad, which increases foreign claims on its future output.

This dependence on foreign money can make an economy vulnerable. If those global investors suddenly get nervous and pull their money out, it could spark serious instability. Managing this kind of financial pressure requires smart thinking, much like the strategies used for effective financial planning for inflation.

The Counterargument: A Sign of a Strong Economy

But hold on—many economists see a different story. They argue that a trade deficit isn’t automatically a problem. In fact, it can be the natural result of a healthy, growing economy. This view focuses on what a deficit says about consumer confidence and economic vitality.

For starters, a deficit often signals strong consumer purchasing power. When people feel good about their finances and have more money to spend, they buy more stuff, including products from other countries. This access to a wide variety of affordable imported goods can significantly improve their standard of living.

A deficit can also be tied to a strong currency. When a nation’s currency is valuable, it makes imports cheaper for everyone, which helps keep a lid on inflation. At the same time, it tells you that international investors see the country as a good place to put their money. From this perspective, a trade deficit isn’t a sign of failure—it’s a byproduct of success.

Answering Your Top Questions on Trade Deficits

Even after diving into the mechanics, it’s natural to have some lingering questions about what trade deficits really mean for a country. Let’s tackle some of the most common ones head-on and clear up a few persistent myths.

Does a Trade Deficit Mean a Country Is “Losing Money”?

This is probably the biggest misconception out there. A trade deficit isn’t like a company’s profit-and-loss statement showing red ink. It’s an accounting of physical goods and services, not a measure of national profitability. All it means is that a country is buying more from the rest of the world than it’s selling to it.

Think of it this way: the money to pay for those extra imports has to come from somewhere. That’s where the capital account surplus comes in. It reflects foreign investment flowing into the country—people and institutions abroad buying up assets like stocks, bonds, and real estate. So while a trade deficit means a country owes more to others, it also often signals strong global confidence in its economic future.

How Can a Country Shrink Its Trade Deficit?

Governments have a few levers they can pull to try and influence the trade balance. Some of the most common strategies include:

- Boosting Domestic Savings: Policies that encourage citizens and companies to save more can reduce overall consumption, including the demand for imported goods.

- Promoting Exports: This can involve negotiating new trade agreements or supporting industries that sell goods and services abroad.

- Currency Devaluation: Some countries might try to weaken their currency intentionally. A cheaper currency makes a country’s exports more affordable for foreign buyers, while imports are more expensive for domestic consumers.

Then there are more confrontational tools like tariffs. Although countries occasionally employ these protectionist measures, they pose significant risks. They often backfire, provoking retaliation from trade partners and creating chaos in global supply chains.

A country’s external surpluses and deficits are mostly homegrown. They are ultimately determined by macroeconomic fundamentals like domestic savings and investment, not just trade policy.

Is a Trade Surplus Automatically a Beneficial Thing?

Not always. On the surface, a surplus looks great—it means a country is a powerhouse exporter. But a large, persistent surplus can also be a red flag for weak domestic demand, suggesting its citizens aren’t consuming enough.

In some cases, a surplus is the result of keeping a currency artificially undervalued to gain an unfair competitive advantage. This can understandably lead to friction with other countries. Ultimately, most economists agree that a state of relative balance, without extreme deficits or surpluses, fosters a healthier and more stable global economy for everyone.

At Global Insight News, we provide the data-driven analysis you need to understand complex economic trends like the trade deficit. Stay informed with our real-time coverage and expert insights. Explore our reporting at https://global-insight-news.com.